Avital Sagalyn was an American artist whose works in oil paint, ink, watercolor and gouache, among other media, speak in a singular voice, distinct in their power and perspective. She has been called an "undiscovered" great talent among 20th century artists. Despite gaining early notoriety, she chose to keep her artworks largely private.

Until now. Shortly before her passing in May 2020, this original and inventive artist flung open her studio doors. In this treasure trove of paintings, drawings and sketches, we witness her extraordinary range. Avital's later works in the United States and France are as fresh and exciting as the peeks she offers into mid-20th century life in Paris, Gordes and Provincetown, among other settings. Her first solo retrospective exhibition opened in October 2019 at the University Museum of Contemporary Art in Amherst, Mass.

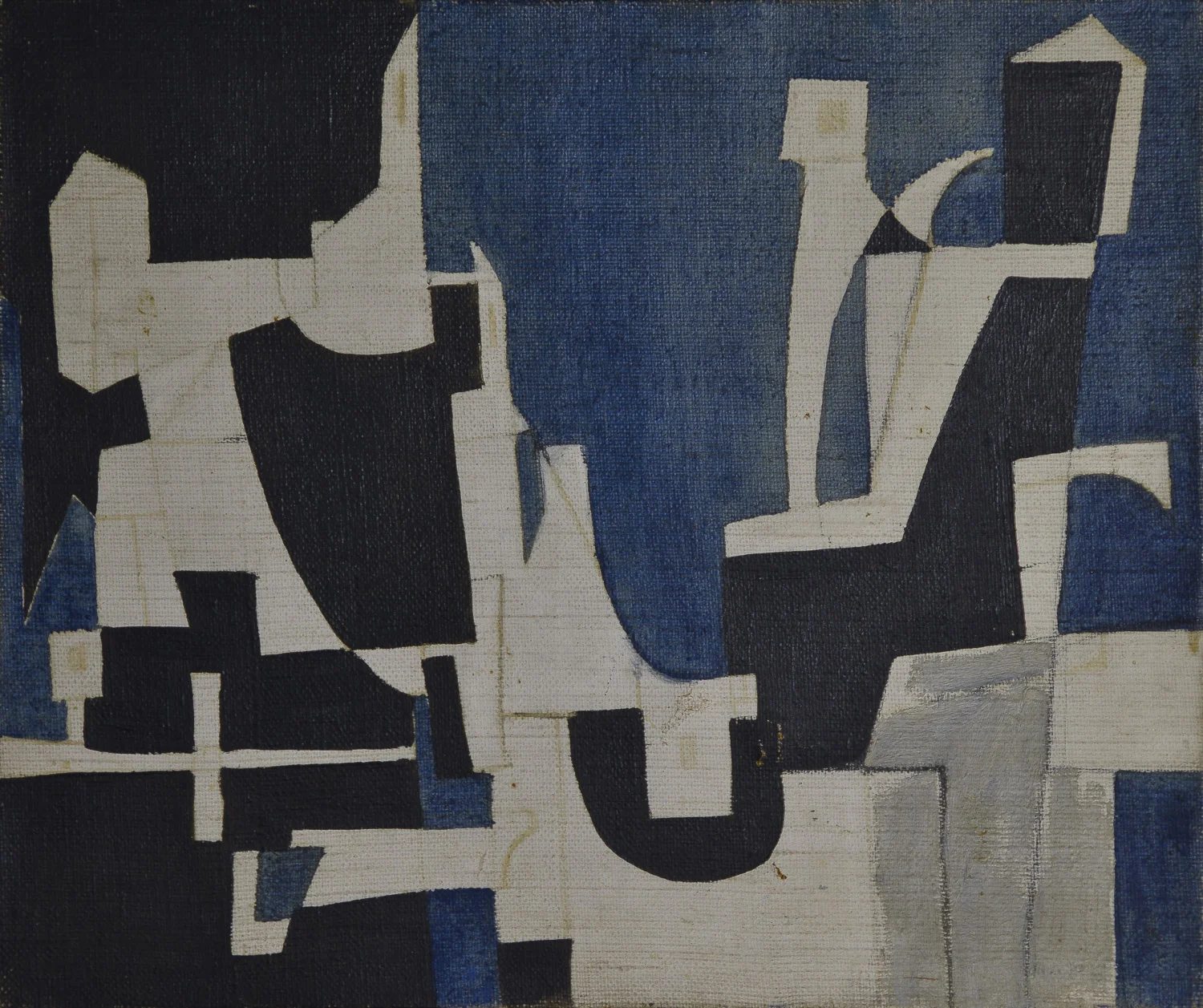

Avital's rich cultural history spanned three continents. Her artistic legacy includes haunting works completed as a teenage refugee during and after World War II; colorful cubist still lifes of fashion mannequins; the post-war Notre Dame veiled by a Parisian haze; mosques rendered abstract and drenched by the Israeli sun; and wharfs of Provincetown, Massachusetts, reduced to an exquisite cacophony of ink strokes.

Her style has sometimes been called "abstract expressionism." But as an original artist who defies trends and artificial limitations, Avital has consistently resisted categorization. Her drawings and sketches remarkably capture the core of her subject matter -- regardless of whether it is a cathedral, a restless crab, a tabletop or a man on a horse.

"I am interested in the essence, not exactly the reality," she said in a 2017 interview. "I always try to get the essence, so that it's more the horse than the horse itself."

Avital cited a number of key artistic inspirations for her work. Among them was Pablo Picasso, whom she befriended while on a Fulbright scholarship in Paris. Avital admired how radically his work evolved from realism to cubism and ultimately to abstraction, presaging the dexterity with which she herself went on to cross style boundaries.

Avital's longtime immersion, too, in the works of J.M.W. Turner is evident in her deft treatment of light, color and brushstroke. She also was affected by Paul Cézanne's purposefully "unfinished" still lifes and his use of negative space.

"I often paint the same subject many times,” she said. "It's a variation on a theme. And once I achieve what I really wanted to say, I stop painting it."

Her work has captivated fine-art contemporaries and critics since arriving in New York as a young refugee.

Born Avital Rachel Schwartz, she had one older brother, Daniel. Their primary language growing up was French, but she and her family also spoke Russian and Hebrew. Avital's maternal uncle, Samuil Marshak, was a renowned Russian children's writer and translator of Shakespeare, Burns, Blake, Keats and Yeats.

Avital's family fled the Nazi invasion of Belgium in 1940. Their journey took them through France, Spain and Portugal. The following year, Avital and her family immigrated to the United States and settled in New York City.

She showed early promise as an artist. The legendary Columbia University art historian and critic Meyer Schapiro, introduced to Avital when she was still in high school, compared her work to that of Turner, the English painter best known for his land- and seascapes. Avital was selected by her high school to attend “Art Classes for Talented Students” at the Museum of Modern Art on Saturdays. One of her drawings from this class, "The Horror of War," was briefly on exhibit at MOMA. Avital also spent many hours roaming MOMA's galleries and absorbing new insights into modern art.

At the time, New York was vibrant with an influx of European intellectuals and artists, taking refuge from the war. Avital absorbed this creative energy, which deeply affected her for years to come. Visiting Avital's parents when she was in high school, Marc Chagall viewed some of her paintings and exclaimed, “This work is very daring. Even I wouldn’t have dared.”

In what was to become a pivotal turn, Avital was accepted to the highly competitive Cooper Union School of Art, from which she later graduated. Lectures she attended on philosophy and literature at the New School for Social Research also influenced her perspectives as an artist. She spent two summer breaks in Provincetown, Mass., a seaside village with a lively community of Portuguese-speaking fishermen and visiting artists. It was here that Avital embarked on some of her most engaging atmospheric works, including simple fishing boats bobbing at harbor amid a shifting fog, and others in which a setting sun merges a placid sea with yellow sky.

Silvia Braverman, then a fashion design teacher at Cooper Union, introduced Avital to Ken Scott, a prominent fabric designer. Avital immediately began designing bold and colorful abstract patterns for draperies. When Scott sent Avital to his agent, however, she was rebuffed. “I can’t sell this," Avital recalls the agent saying of her abstract paintings for textiles. "You are ahead of your time.”

After college, Avital spent a year in Paris and, in 1949, applied for a Fulbright scholarship to study painting in France.

Schapiro, the revered Columbia University art critic, served as a reference for Avital's application, predicting she had the potential to become one of the great painters of the 20th century. A second reference was from Charles Sterling, a longtime Louvre painting curator who spent the war years at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Avital became one of the first women to receive a Fulbright scholarship to study painting abroad. She did so at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris between 1949 and 1950.

She met Picasso through a mutual friend and fellow painter, Manuel “Manolo” Ángeles Ortiz. Initially, Avital demurred on an introduction, disinclined to give even the appearance of chasing fame. But Ortiz convinced her that Picasso was aware of her work and interested in meeting her as a contemporary artist. In a visit at Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler's Paris gallery, Avital and Picasso hit it off straightaway and he invited her to visit his studio.

A few weeks later, upon arriving at the Paris studio, "I immediately recognized the concierge," Avital said. "He painted her during the war with three eyes." Meeting Picasso's model in person, Avital was struck by the intensity of the assistant's gaze. She actually "looked as if she had three eyes," Avital marveled.

At Picasso's invitation, Avital also visited him at his ceramics workshop in Vallauris, in southern France. Introduced by colleagues, sculptor Constantin Brâncusi also befriended Avital and hosted her many visits to his Paris studio. As well, she met fellow American Morris Graves, a West Coast native and member of the Northwest School of Visionary Art.

Initially, Avital lived in Paris's Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighborhood, at the time the city's hub for painters and other artists to meet. She later lived in an apartment owned by an acquaintance in the high-fashion industry, on Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in the 8th Arrondissment. The interior, populated by mannequins and lined with three-way mirrored walls, can be seen in several of Avital's brightest cubist abstractions and refined pencil line drawings from this period.

Her work drew notice in Paris. Gildo Caputo, owner of the prestigious Gallerie de France, was among many in the city's creative community who took great interest in Avital's compositions. Art historian Pierre Francastel and art critic Charles Estienne also lauded her work.

Although Parisian art circles at the time were dominated by male painters working in the “lyric abstract” and “art informel” movements, “the terms set by these men helped Avital find her own direction, as a truly free artist,” writes UMASS Amherst art historian Karen Kurczynski in a 2019 exhibition catalogue essay titled, “Avital and the New School of Paris, ca. 1950.” “Avital’s paintings were intuitive and spontaneous responses to the scenes she observed. Her works convey the connection between a subjective viewpoint and an object or scene in the world.”

After three years in Paris, Avital returned to New York. Beginning in 1951, she taught children's art classes at MOMA's People's Art Center.

Avital was among few women in Manhattan's male-dominated art scene of the 1950s. She occasionally attended events that "New York School" painters held at a club on 8th Street, meeting several fellow artists who became friends and acquaintances. Among these were abstract expressionist painters Willem de Kooning and Richard Pousette-Dart. Perhaps Avital's greatest artistic kinship at this time was with her college-years friend Reuben Tam, a native Hawaiian painter and poet living in New York.

“I think Avital’s work from the late ‘40s and the early ‘50s, when she was only shortly out of Cooper Union — a very young artist in her 20s and 30s — was on a par with a lot of the very best artists making work both in Paris and New York at that time,” Hugh Davies, former director and CEO of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, said in a February 2020 interview. “She was breaking new ground in her atmospheric paintings that combine cubism with the lessons learned … from Turner in terms of light, and also from the impressionists.”

Davies added: “It was a kind of abstraction … which incorporated emotion and perception and phenomenology in a way that was very refined and very appealing.”

The well regarded Artists Gallery on Manhattan's Upper East Side offered Avital a one-woman exhibition, and NYC gallery owner Sidney Janis also voiced interest in seeing her portfolio. However, she declined, concerned that she wasn't ready and wanting to avoid any commercialization of her work.

In the summer of 1952, Avital was accepted into the MacDowell Colony, a prestigious artists' retreat in Peterborough, New Hampshire. There she created dozens of joyful and spare renderings of vases and jugs. Avital’s other MacDowell works included pen and ink drawings of plants, some on music-notation paper given to her by Jacob Avshalomov, a composer and conductor who was resident at that time. Also at the retreat was Hyde Soloman, an abstract painter Avital had met years earlier in Provincetown, and who had helped found the Jane Street Gallery, an artists' collective in Greenwich Village.

In 1955, Avital married Robert Sagalyn, at the time an off-Broadway theater producer and actor. His productions included "The Frogs of Spring" (1953) and "The Trial of Dmitri Karamazov" (1958). Robert also stage-managed and appeared in a 1952 Broadway production of "Mrs. McThing," starring Helen Hayes and featuring Ernest Borgnine.

A gregarious intellect who later helped found the International Center for Photography in New York, Robert supported Avital's painting career from the start. Upon coming home in the evening, he'd often say, "I love smelling turpentine even more than the smell of soup."

Together they had three children: Michelle, Adine and Daniel. Shortly after their third child was born, Avital resumed teaching at MOMA. In 1968, Avital and her family moved to Amherst, Massachusetts.

There Avital served on a search committee to hire the first director of the Fine Arts Center at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She also participated on a separate university panel to select works of art for the museum to purchase.

Avital and her family were devastated by Robert's sudden death in 1985 following a heart attack. For years, she only rarely felt inspired to draw or paint. With the turn of the century, though, came renewal.

Later in her decades as a resident of western Massachusetts, Avital showed no sign of diminished curiosity, interpretative genius and breathtaking invention. In her 2019 solo exhibition, “Avital Sagalyn: A Life of Exploration,” three University of Massachusetts Amherst student curators worked with their art history professors and the artist to showcase more than 55 of her paintings, drawings, sculptures and textile designs. The Boston Globe lauded Avital’s work in an Oct. 13, 2019, review of the three-month exhibition.

“I think what impressed me the most was the fact that she has kept her own path, this incredibly distinctive style, and that she has kept her own vocabulary,” University Museum of Contemporary Art Director Loretta Yarlow says in a foreword to the exhibition catalogue. “Avital has had an inner strength, and it comes out through her work that I find really defies categorization.”

Avital’s later works run from jazzy gouache portrayals of the Manhattan skyline to modern pencil renderings of oversized mosquitos -- created as the Zika virus stole headlines and lives -- to sketches that motion-freeze seagulls midflight along the Connecticut shore. A number of Avital’s original pieces from across decades of work became available for purchase at PULP Holyoke gallery beginning in 2020. PULP showcased Avital’s exquisite and inventive use of line throughout her work in a solo exhibition that opened in May 2021, “Avital Sagalyn: Ligne In.” The title echoed Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg’s 2013 bestselling book, “Lean In,” which encouraged women to embrace their passions without regard to gender norms. Avital lived that proposition six decades before the book was published.

In September 2023, the UMCA contemporary art museum in Amherst featured three of Avital’s works in its permanent collection to appear in an exhibition, “Artists, Born Elsewhere.” The museum said its nearly three-month display was of works by “artists who immigrated to the United States and have had a lasting impact on American culture.”

Gallery A3 in Amherst selected Avital’s pencil-on-paper rendering, “Dead Bird No. 1,” for its 9th Annual Juried Show in August 2024, “Impermanence.”

This was followed by an October-November feature by PULP Holyoke, Mass., of two 2016 works titled “Mistral Wind, Mediterranean in Provence,” marker on paper, in its back gallery.

Inclusion in these group exhibitions was followed by the University Museum of Contemporary Art’s curation of “Dead Bird,” ca. 1990s, pencil on rice paper, from its permanent collection, for “(OFF)BALANCE: Art in the Age of Human Impact,” open March 27 to May 9, 2025.

Today, regardless of the medium, Avital's artwork continues to defy time and astonish viewers.

"I think real artists never really get old," she said in a 2019 interview. "There's always a surprise and discovery."

This biography was written by Avital Sagalyn's family. Copyright © 2017 and as updated.